Legendary interior designers from every decade of the 20th century

Legendary interior designers from every decade of the 20th century

”Thinking about design is hard, but not thinking about it can be disastrous,” Ralph Caplan, the long-time design columnist and editor of I.D. magazine, told Debbie Millman on her long-running podcast “Design Matters.” Caplan certainly had it right.

Interior designers fall on the front lines of keeping such disasters at bay by envisioning and creating spaces for people to use and enjoy. Be it a residence, restaurant, museum, hospital, or shopping center, there are practical and aesthetic concerns for designing functional, beautiful, and successful interiors. “For a house to be successful, the objects in it must communicate with one another, respond and balance one another,” Andrée Putman, the French designer whose work at New York’s Morgans Hotel helped launch the popularity of the boutique hotel in 1984, told LuxDeco.

Dorothy Draper, the grande dame of decor, had another approach: “I always put in one controversial item. It makes people talk.” Whether the desire is for comfort and safety or shock and conversation, interior designers influence the smallest of our daily actions and the largest of cultural zeitgeists.

While all designers have influence, what makes a legend? Name recall is certainly one consideration, but it shouldn’t make up the whole of it. Some prominent names of the last century are missing on this list—Jean-Louis Deniot, Billy Baldwin, Parish-Hadley—but in their place, an opportunity opens to highlight the work of interior designers who have also forged a singular path, whose visions created work with an enduring effect today. A few even opened the doors—a much-needed and difficult gesture in the rarified world of interior design.

With this in mind, Lazzoni Modern Furniture scoured publications like The New York Times and The New Yorker, museum exhibitions, and design magazines like Architectural Digest and Veranda to highlight 10 of the most influential interior designers from each decade of the 20th century.

![]()

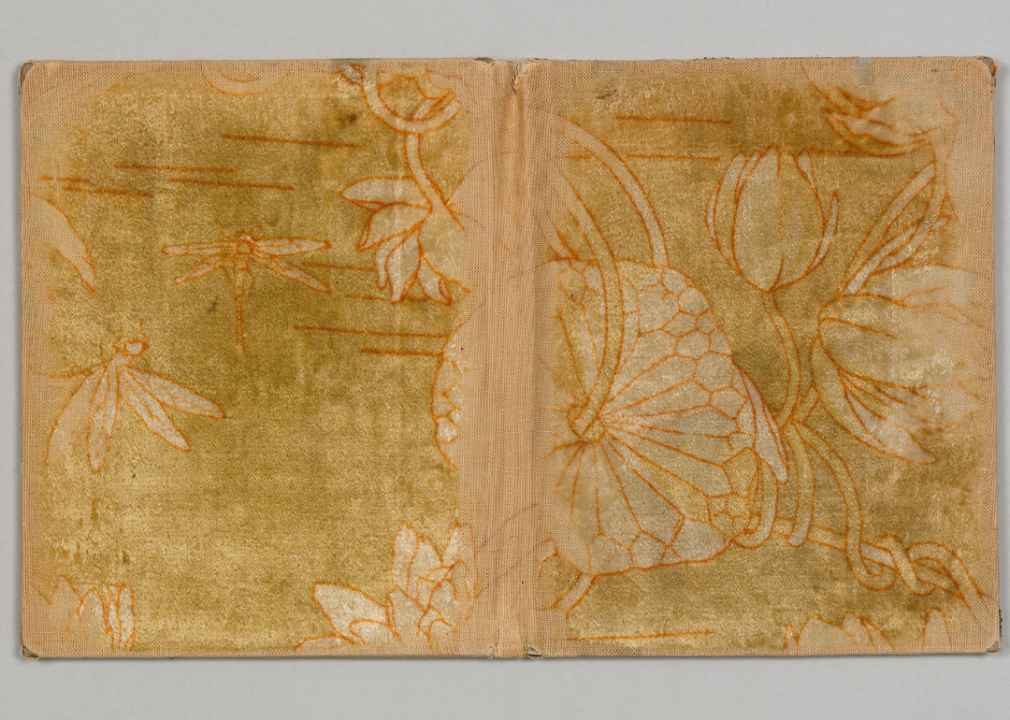

1900s: Candace Wheeler

Considered one of the first professional interior designers, Candace Wheeler is often called the “Mother of Interior Design” for her role in establishing the field and encouraging other women to enter it.

A middle-class woman and feminist, she believed in the power of the pocketbook. She began her career as an advocate for women to use their skills in the decorative arts to create businesses they could independently own through the Society of Decorative Art.

With three other designers, including Louis Comfort Tiffany—a scion of the famed jeweler Charles L. Tiffany—she formed Associated Artists, a design firm that began in 1879 and dissolved in 1883. Wheeler specialized in textiles and, over the years, worked with celebrities like Cornelius Vanderbilt II and literary greats like Mark Twain. Wheeler’s remarkable career spanned the 19th century to the 1920s, and she encouraged many women designers to follow in her wake.

1910s: Elsie de Wolfe

Like Candace Wheeler, Elsie de Wolfe is often credited as the first interior designer. Her long and trailblazing career similarly resulted in a prominence that opened the design field to other women.

While Wheeler predates her, de Wolfe, a professional actor who started in interior design with a 1905 commission for New York’s Colony Club, organized by powerful women of the times with names like Astor, Morgan, and Whitney.

Perhaps that’s due to her sheer audacity to disregard convention in favor of doing things her way—in life and art—a tendency enabled by her wealth of social connections thanks to class status. In any case, her design for the club eschewed the usual drab and formal Victorian atmosphere for a casual and light style full of whimsy and cemented her as the go-to decorator for high society—clients included Henry Clay Frick and the Duke and Duchess of Windsor.

By the teens, she had commissions around the country, a New York showroom, and a loyal following of fans for her books that brought her elan to a mass audience.

De Wolfe’s legacy remains strong thanks to the many elements she introduced into design vocabulary that are still prevalent today—mirrors, chintz, and decoupage were all signatures—and because of all the designers she mentored and inspired.

1920s: Eileen Gray

Irish designer and architect Eileen Gray deserves to have her name mentioned with Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, and Marcel Breuer as a master of modernism. Not only did she work with several of these men, but she also pioneered the svelte use of chrome and steel in furniture alongside or—in the case of Le Corbusier—ahead of them.

After first studying drawing and painting, she apprenticed under expert Seizo Sugawara to learn the difficult technique of Japanese lacquer. Gray then used these skills in her interior commissions, including the fabulous Rue de Lota apartment she designed for Juliette Mathieu-Lévy. Gray created the carpets and much of the furniture for the home, including her famed bulbous Bibendum chair, whose name was inspired by the Michelin Man. The chair is still in production today. Gray sold her chic creations in a shop she owned under the name Galerie Jean Désert, which masked her gender.

While the importance of her work went mostly unrecognized during her life, Gray’s contributions, including her E-1027 house in southeast France and the adjustable E-1027 table she designed to go in it, are now regarded as great achievements in humanizing and transforming modernism’s austerity so it better meets the needs of actual humans.

1930s: Harold Curtis Brown

It remains difficult to accurately document and understand the influence of Black interior designers due to the systemic racism these creatives have faced in America. Despite being denied access to mainstream success, many early Black interior designers made lasting contributions to the field, work that is being uncovered by historians like Michael Henry Adams, author of “Style and Grace: African Americans at Home.”

A classically trained designer who worked in Paris and Washington D.C. before coming to New York City, Harold Curtis Brown created the interiors for some of the most famous jazz clubs of Harlem during the Renaissance era, including the legendary Cotton Club. Along with several other nightclubs, Brown also designed the interiors of the Hotel Navarro, a 25-story building constructed in 1926 that was transformed into a Ritz-Carlton hotel in the 1980s.

For a designer in the middle of his career and gaining increasingly important and expensive commissions, something odd happens in 1938: Brown disappears. Adams believes the designer may have started passing as white to further his career.

Nearly a century later, there are more prominent Black designers than ever (Cecil Hayes, Sheila Bridges, Nicole Gibbons, and Brigette Romanek, to name just a few). Still, a continued need for more diversity in the industry remains.

1940s: Dorothy Draper

Like many early interior designers, Dorothy Draper came from a privileged upbringing, and she smartly built the advantage of her wealth and social status into her business from its start in 1923.

Entirely self-taught, she cut a glamorous figure with her fashion and had an unfailing sense of her own style, a confidence that gave her the gumption to create the one thing she wasn’t supposed to have: a career. From her first big hotel commissions in the 1930s (Carlyle Hotel, Hampshire House) to her most recognized and enduring work, her massive redesign of the Greenbrier resort, Draper’s trademark “modern baroque” design changed what good taste looked like and, in the process, created Hollywood Regency. Some of Draper’s signatures included bold and audacious color pairings, black-and-white floors, ornate moldings, lots of chintz, and brightly painted doors.

Her visionary designs for her corporate clients included everything from the décor to menu design, staff uniforms, and even matchbooks. Many of her creations remain iconic today—elaborate mirror frames, the birdcage chandeliers she installed at the Met’s restaurant, and, of course, cabbage rose chintz.

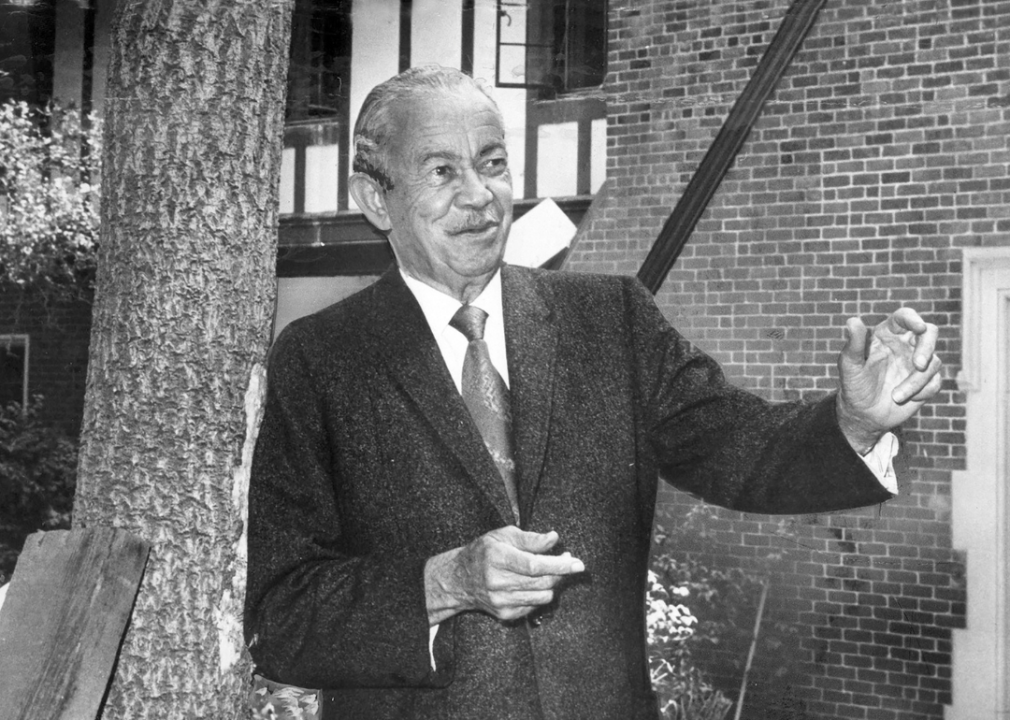

1950s: Norma Williams Harvey

As the lead interior designer in Paul Revere Williams’ architectural firm, Norma Williams Harvey is a rare, known example of a Black designer of prominence before the Civil Rights Movement.

Norma worked for her father, Paul (pictured), one of the most influential architects in Los Angeles and the first Black American member of the American Institute of Architects. He designed more than 2,500 buildings across LA and beyond, and was deemed “the architect to the stars” for his work with such Hollywood clients as Cary Grant, Danny Thomas, Lucille Ball, and Desi Arnaz.

One project Norma led interiors on was a hilltop bachelor pad for the newly single Frank Sinatra on Bowmont Drive in Beverly Hills. The singer wanted a hip, state-of-the-art house built around the living room’s audio system. Norma, who provided all the furniture and decor, took the Japanese modernism of her father’s concept (room dividers rather than walls) and enhanced the drama with a striking contrast in colors (white sofas, lacquered furniture in high-gloss reds, oranges, and blacks).

When the home was featured on the television program “Person to Person” and Sinatra led a tour, he remarked on several personal items her keen eye had set prominent in the house, such as a photograph of his three children. The show, like the house, was a huge hit.

1960s: Florence Knoll

Perhaps no designer had more lasting influence on the look and function of the corporate office than Florence Knoll, who revolutionized the workplace with her sleek, thoughtful designs that remain ubiquitous today.

Knoll was a protégé and family friend of modernist architect Eliel Saarinen. When Knoll became a partner in her husband’s furniture company in the 1940s, she brought her Bauhaus influence, innovative thinking, and rigorous work ethic, founding the in-house design studio known as the Knoll Planning Unit.

Her philosophy of “total design” took a holistic approach to creating environments prioritizing transparency, flexibility, and utility, and she pioneered large, open workspaces over private offices to create modern and inviting offices.

Some of the largest corporations of the time—IBM, CBS, General Motors—served as clients. She created many iconic designs that are still in production today and commissioned two of the most familiar pieces of modern furniture: the Bertoia wire chair and the womb chair from her friend Eero Saarinen.

In 1964, The New York Times called her “the single most powerful figure in the field of modern design.” Her trailblazing influence remains today, with museums collecting her work and Knoll’s catalogs still showcasing her designs.

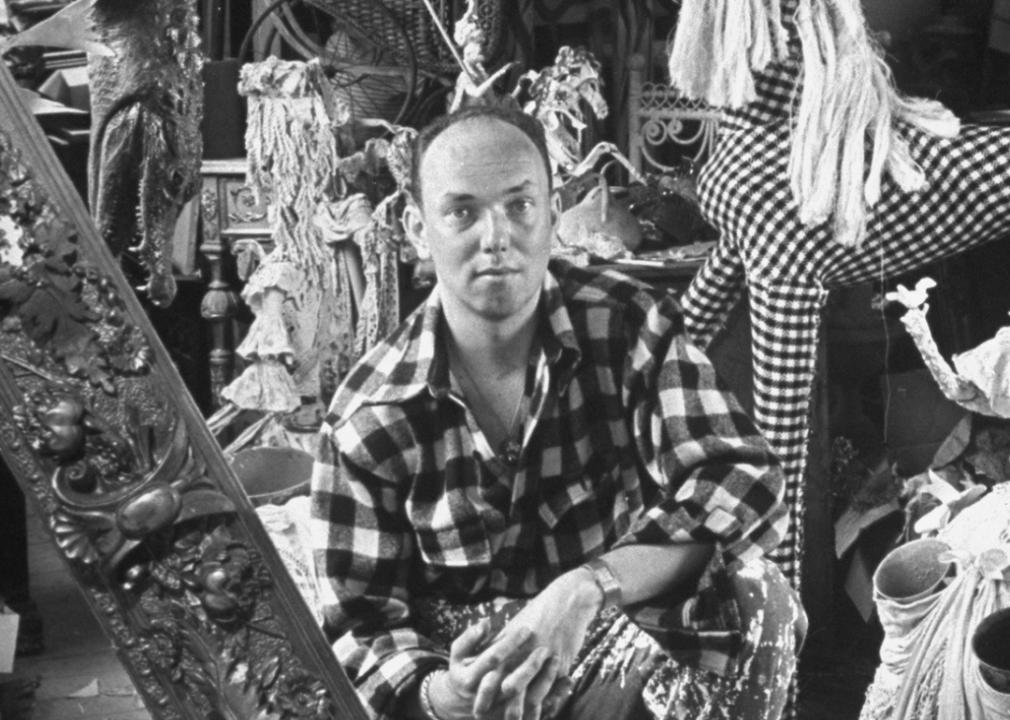

1970s: Tony Duquette

A maximalist icon in design and life, Los Angeles-born Tony Duquette had design in his blood—his great-uncle worked with William Morris, and Duquette’s own patron was none other than Elsie de Wolfe.

After working as a store designer in the 1930s, he began freelancing for some of Hollywood’s hottest interior designers, like William Haines and James Pendleton. He also worked in the film business, creating costumes (with Adrian) and sets.

Tinseltown’s magic was part of Duquette’s design DNA, and his work is known for transforming mundane objects like dollar-store objects and mirrors into luxurious designs. After opening his salon in the 1950s with his wife, whom he called “Beegle,” guests included a who’s who in Hollywood, from Aldous Huxley to Greta Garbo.

Throughout the 1960s and ’70s, Duquette traveled throughout Europe, the Americas, and sometimes beyond. His clients included influential patrons of arts such as Doris Duke, Norton Simon, and J. Paul Getty. They loved his dramatic use of color, his “more is more” opulence, and his utter originality—and for decades, he traveled the world on commissions, creating theatrical interiors, beautiful jewelry, and his crowning achievement: his Dawnridge estate.

No other designers’ work epitomizes the bohemian excess and enchantment of the decade as much as Duquette’s, and his designs continue to inspire today—fashion icons Tom Ford and Kelly Wearstler both cite him as an influence.

1980s: Mario Buatta

Known as the Prince of Chintz for his frequent use of floral fabrics, Mario Buratta created a look that could be called shabby-chic if it didn’t make it sound cheap. Working for wealthy and stylish clients such as Mariah Carey, Malcolm Forbes, and Billy Joel, Buatta’s interiors projected comfort and luxury—and they were full of expensive antiques.

Like Tony Duquette, the Italian American designer began his career working for a department store and then under the tutelage of other prominent decorators—in this case, Rose Cumming and Dorothy Draper. However, the work of British designers John Fowler and Nancy Lancaster seemed to have most inspired Buatta, who took their English country house style and made it his own with chintz upon chintz, saturated colors, ruffles, and frills.

Instead of the austere minimalism of the 1960s or the wild experimentation of the ’70s, Buatta’s designs are all ’80s Anglophile exuberance: think Laura Ashley dresses, the Regan presidency, and a Lady Di obsession all wrapped up in chintz and tied with a bow.

1990s: Kelly Wearstler

Just as certain architects like Frank Gehry are “starchitects,” some interior designers are household names—and Kelly Wearstler is certainly one of them. Known for her bold designs, Wearstler’s unique sensibility incorporates everything from mid-century modern and Hollywood Regency to Tony Duquette-style baroque.

Her role in the late 2000s as a judge on the popular TV show “Top Design” granted her celebrity status beyond the design world, but it was in 1995 that the design behemoth got her start by opening her own interior design studio. In that same decade, she would meet Brad Korzen, a hospitality developer in need of a keen eye for interiors to revive the sorry state of his newly purchased properties, including a 1949 Avalon hotel-turned-retirement home and a boarding house in Beverly Hills, California. Wearstler delivered and won acclaim for a series of projects in the 2000s that would set a new standard for high-end boutique hotels.

The spirit of the 1990s pervades her work in that it’s hard to pin down her wide-sweeping aesthetic that borrows what it likes from the past and reconfigures it with an edge. Whether it’s one of her many hotels, homes, or retail environments or an object from her extensive line of products (textiles, lighting, furniture, and even fashion), Wearstler’s creations are instantly recognizable as hers—it’s a look that’s proved popular, making her one of the most sought-after contemporary designers of the 21st century too.

Story editing by Carren Jao. Copy editing by Paris Close.

This story originally appeared on Lazzoni Modern Furniture and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

Provided by Stacker